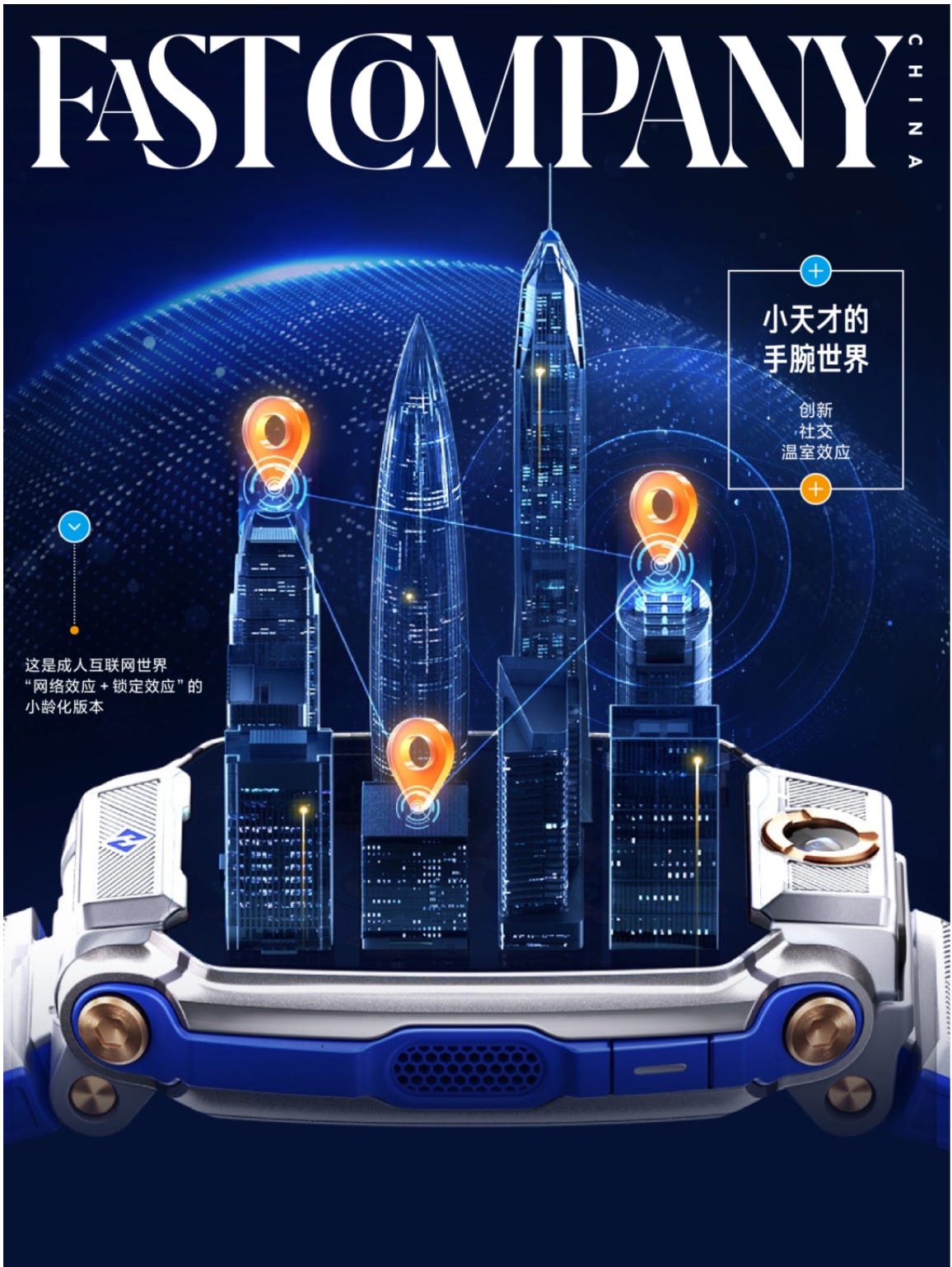

China's Apple Watches for Kids

Brilliant dopamine-fueled marketing, and the darker long term implications of Little Genius Watches

Over the summer in China, I found one thing impossible to miss: the ubiquity of watches on children’s wrists. These are smartwatches, functionally Apple Watches, but in shiny metallic blues and pinks, and kids as young as five are swiping and chatting via voice messages on them.

My nieces and nephews play make-believe store at home and there is no physical money involved. They hold out their arms to me and the watch pops a QR code. I scan with Alipay or WeChat Pay, give them real money, and the game goes on.

The watch is also the screen you do not put down, because for children in China, their social life now lives on their wrists. The category leader is Little Genius, 小天才, branded as imoo outside China. I wanted to understand how these watches took the market, the long-term implications for kids, and the China context that allowed this market to flourish.

To fully investigate, I wrote about Little Genius watches for Fast Company China. Below is translated in full and lightly smoothed for English flow. If you read Chinese, the original is here: https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/sGNwbPoyrjBvwC4pt1yLAw.

Little Genius’s Wrist-Sized World: Innovation, Social Life, and the Greenhouse Effect

Fast Company China Edition · by Ivy Yang · September 1, 2025

Over the past decade, tech products for children and teens have evolved from study devices and handheld game consoles to wearables, with features piling up and category boundaries blurring. Today’s children’s smartwatches are at once a communication tool, a health monitor, a locator, and a pocket-sized social terminal.

IDC reports that in the first quarter of 2024, shipments of children’s smartwatches in China rose 44.4 percent year over year to 4.04 million units. This market is expanding against the cycle and moving upmarket at the same time. The brand that dominates is Little Genius. According to RUNTO’s first-half report on China’s children’s smartwatch market, Little Genius leads with a 35.3 percent share, ahead of Huawei at 12.2 percent and Xiaomi at 9.4 percent. Its newest flagship model sells for up to 2,399 RMB. Pricing now sits alongside adult devices such as the Apple Watch, and because Little Genius reserves many of its newest features for its latest Little Genius models, faster hardware cycles drive repeat purchases and strong lifetime revenue. Given the size of China’s under-15-year-old youth population, the runway remains long.

Beyond the numbers, Little Genius is more than a commercial winner. It functions as a live digital-social experiment among young users, testing how a closed platform can reshape relationship networks and day-to-day interaction before those users are fully grown.

Founder Jin Zhijiang emerged from the BBK ecosystem shaped by Duan Yongping. BBK, short for Bubugao步步高, began in the mid-1990s in Dongguan making educational electronics and audio-visual products, then expanded into mobile phones and incubated the brands OPPO and vivo. Before BBK, Duan led Subor, known in Chinese as Xiao Bawang 小霸王, a 1990s household name for inexpensive learning computers and gaming devices that put educational electronics on millions of desks. Duan’s operating playbook emphasized tight product focus, channel discipline, and building defensible moats. Pinduoduo founder Huang Zheng, also known as Colin Huang, has publicly credited Duan with hands-on guidance on product positioning and release cadence. In plain terms, what to build for whom, at what price, and when to ship.

Shaped by that lineage, Jin internalized a philosophy of locking onto core pain points and building defensible moats. During his BBK years he developed first-hand intuition for how children’s needs were shifting. Around 2010, when mainstream options were still clunky candy-bar phones or single-function trackers, he began betting on children’s wearables.

In children’s electronics there is a structural reality. The buyer is the parent, the user is the child, and their needs often pull in different directions. Winning means balancing both. That is where Jin’s playbook gives Little Genius leverage. For parents, emphasize safety and control. For kids, deliver social life and a sense of identity. For the brand, build moats with a closed ecosystem and high-frequency iteration.

Unlike adult watches that focus on reminders and logging, children’s watches are engineered as pocket-sized social systems. They are the channel kids use between schoolwork and daily life to keep in touch with peers and to explore online friendships. In Little Genius’s world there is no WeChat. There is the Little Genius watch community. Adding and expanding friend lists, posting updates, trading likes, and tagging into topics all happen inside Little Genius’s digital walls, creating a digital space largely free of adult interference.

For parents, Little Genius offers precise location tracking down to building floors, permission controls and usage windows, plus heart-rate and activity monitoring. That produces a feeling of visibility and control. On the commercial side, hardware plus features reserved for new models, limited editions, and collaborations create repeated purchase moments. In some ways, Little Genius is shifting from device maker to operator of the social infrastructure of childhood.

In informal interviews, most parents answered the “why this brand” question the same way: the children say all their classmates use Little Genius. Alternatives exist, but once school is in session, Little Genius is the social currency that matters.

This choice reflects a careful balance. In a parent’s frame, all-day scrolling on a phone or short-video app reads as a failure of supervision, so a watch with constrained functions and controllable permissions feels like a lower-risk on-ramp to the digital world. From the child’s perspective, Little Genius is the key to class group chats, to posting updates, and to the ordinary interactions that stitch the peer group together.

Inside this greenhouse, kids learn to thumb-type on a tiny screen, take selfies with the front camera, and sometimes pop the watch face off to get a better angle. Mirroring adults’ WeChat habits, they check in, caption, and post inside their watch community akin to the Wechat Moments interface. More importantly, Little Genius embeds an habit-building rewards loop. Daily check-ins, step counts, and other point-earning actions unlock avatar gear and upgrades. Virtual rewards become reasons to keep the device on and to interact often, reinforcing presence and status within the cohort.

Little Genius also maintains key tenets of a platform. Only users of the same watch brand can add one another as friends. Some content can be exchanged only when both kids have the latest model. Fast iteration and feature thresholds push upgrades. Limited and co-branded editions add status to the hardware itself. Early adopters of a new model get a brief spotlight in class. Special filters or high like counts become sources of envy in school. User habits vary by age, from preschoolers who rely on voice notes to teens navigating more complex XTC circles. Little Genius is no longer just a watch. It is a small world with its own logic.

This is the children’s-scale version of the adult internet’s network effects and lock-in mechanism.

Under the stickiness is a coupled design of perception and reward. Direct touch input folds the screen into the brain’s body map. Multi-touch, swiping, and pinching heighten kinesthetic engagement. Dynamic feeds, likes, and unread badges map onto variable-ratio reinforcement, the same mechanism that keeps slot machines, short-video apps, and social platforms in constant use.

Over time, frequent micro-rewards raise the dopamine threshold. To feel the same level of pleasure, a user needs feedback more often or stronger stimuli. Traditional sources of dopamine for children, such as outdoor play, physical games, reading, and crafts, arrive less frequently and at lower intensity but with longer sustained feelings of fulfillment. When joy mostly arrives as instant feedback at the wrist, low-stimulus activities feel flat. The baseline for pleasure rises quickly, attention and patience fall, and the idea of satisfaction is rewritten. When the reward system is constantly pulled forward, the absence of stimulation can bring irritability and mild withdrawal-like reactions.

Health risks are part of this picture. Parents often assume a smaller screen is safer, yet the usage posture is a high-frequency loop of raise the wrist, stare, and near-focus. That forces rapid shifts between far and near vision and adds strain to a developing visual system. According to the National Disease Control Administration, overall myopia among Chinese children and adolescents in China was 51.9 percent in 2022. Multiple studies identify near-distance, high-frequency, fragmented viewing as a driver of progression. Each feature upgrade adds new reasons to look at the screen longer, which makes intervention harder.

One feature widely welcomed by parents is All-Day Mood. The watch tracks and visualizes a child’s emotions across the day and outputs a positive-emotion share, and then benchmarked against peers. Quantifying joy, calm, and displeasure offers comfort because it feels like a verifiable report card. The question remains. If a watch must calibrate a child’s emotional and health state, how much room is left for common sense and the older intuition of caregiving?

For parents, Little Genius is a safer gate into the digital world. For children, it is the necessary ticket into the peer circle. That sense of safety is also cultivating a greenhouse of digital socialization, where interactions are confined to an environment that looks safe but is highly uniform. Most relationships narrow to the same age, the same school, or the same neighborhood, with little diversity or serendipity.

At the same time, to climb the watch leaderboards quickly, kids engage in mutual boosting and friend-list expansion with strangers, sometimes extending beyond the watch to platforms such as Red Note. Experiences that ought to be learned in real-world encounters are replaced by transactional exchanges, like for like feedback, mutual adds, topic tagging, and vote swaps. The result is social competence that narrows under greenhouse-style protection and discipline. It arrives earlier, runs deeper, and is harder to detect than the information filter bubbles adults face.

Globally, the debate over digital health is gaining urgency. In The Anxious Generation, psychologist Jonathan Haidt argues that faster networks and advancing tech make screen life more immersive, meeting desires with minimal effort while face-to-face time shrinks. The consequences include declining social competence and rising loneliness.

That lens helps explain the Little Genius phenomenon. When a generation’s friendships, social life, and sense of identity are largely carried and shaped by a device worn on the wrist, the long-term effects are unknown. The watch can make kids more fluent in digital spaces. It does not automatically make them more capable in the real world. Little Genius has brought Chinese children into a greenhouse of digital socialization ahead of the curve. Whether that greenhouse is advanced training for the future or a premature loss of real-world experience remains an open question.

So interesting, I know a number of adult friends are now moving to Oura rings, smart earbuds and Woop wearables to move away from screens