Manus Shows How China-Shedding Works

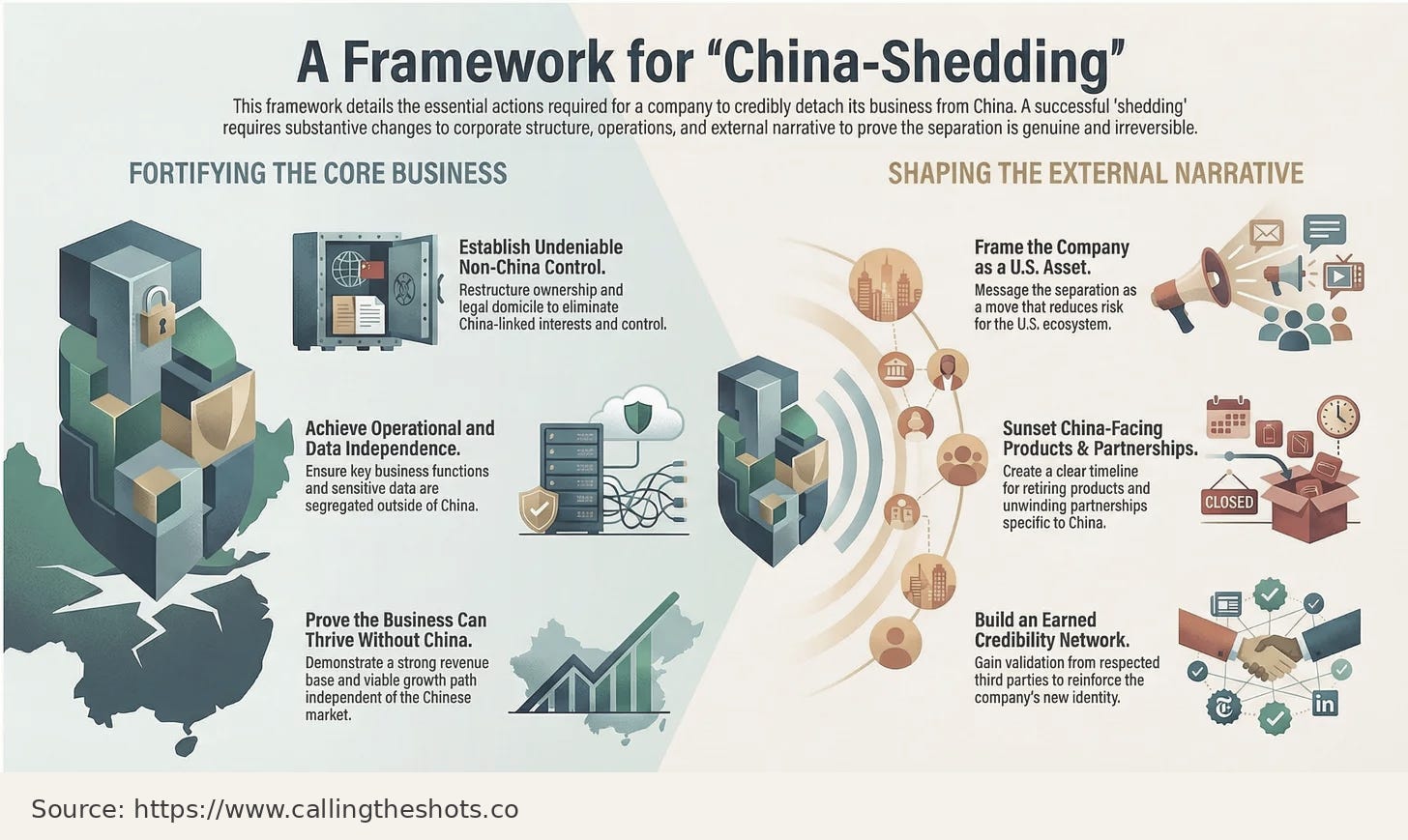

The Manus Meta deal shows how to survive reverse CFIUS: U.S. control, clean cut with China with no room for ambiguity.

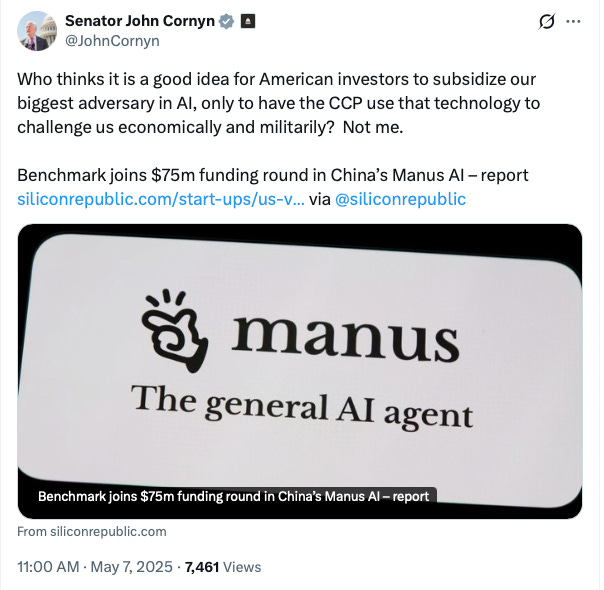

Back in May, when I wrote about Manus while the U.S. Treasury was reviewing Benchmark Capital’s $75 million investment in the company, it was unclear whether “China shedding” actually worked.

By China shedding, I mean the deliberate effort to reduce or remove perceived China ties in order to lower political, regulatory, and reputational risk in global markets. Meta’s decision to buy Manus for $2.5 billion is a definitive vote that China shedding is an exit strategy that can clear at scale, at least on the U.S. side of the U.S.–China AI competition.

To understand why, it helps to define “reverse CFIUS” in plain terms. If CFIUS is the U.S. process that worries about foreign buyers taking control of sensitive American companies, reverse CFIUS flips the direction of concern.

Instead of asking, “Is China buying U.S. tech capabilities?” it asks, “Are we helping China build?” That is why a U.S. investment into a China-linked AI startup triggered scrutiny in the first place. Washington was trying to stop American money, talent, and technical know-how from strengthening AI capabilities that could end up inside China’s ecosystem.

That was the Benchmark story. When Benchmark invested, the political framing was straightforward: why should American capital subsidize an AI company with roots in China?

Meta changes the story because it changes the end state. In the Benchmark case, the headline was “American capital flowing into a China-connected AI company.” In an acquisition with a clean cut with China, the headline becomes “a China-origin capability being pulled into U.S. ownership and control.”

If Chinese ownership is bought out and China operations are shut down, the asset ends up on the American side, it’s not a problem. TikTok is the closest analogy: the de-risking outcome in Washington is not a promise; it is a change in control. Meta went straight to the point: this deal delivers that change, so the transaction removes China-linked exposure rather than extending it.

Meta’s PR strategy around the Manus acquisition

Meta executed the messaging with almost surgical precision, and Manus checked off many boxes in advance by moving to Singapore. Meta left little room for ambiguity, and DC China hawks have not mounted a sustained objection since the announcement.

A Meta spokesperson said there would be no continuing Chinese ownership interests after the transaction, and Manus would discontinue services and operations in China. Reporting also highlighted steps that sounded enforceable rather than rhetorical, including shutting down the China-facing AI assistant Monica.cn, restricting incoming Manus employees from accessing prior customer data, and geo-gating model access.

Timing helped too. The announcement landed in the holiday dead zone, when reporters are away and lawmakers are harder to mobilize. But timing only works when the messaging is already airtight. Meta understands the DC game and has spent decades building a Hill operation for a rainy day. In this case, the rainy day arrived as a China-origin AI acquisition, and Meta came prepared with exactly the language Washington wants to hear.

Why now, and why Manus?

Like many, I listened to Manus’s last long-form interview (CN) before the acquisition. In one of the most illuminating moments from the three-hour conversation, co-founder Peak Ji was asked how a small company competes with OpenAI. He answered with a line that is less a quip than a directional strategy for this AI era: “小公司怎么和大厂竞争,就是赶紧成为大厂.” A small company competes with a giant by quickly becoming one.

He did not mean matching headcount. He meant achieving concentrated superiority in a domain that a platform cares about, then attaching distribution, compute, and compliance to a larger balance sheet through acquisition. Sounds to me like a very clear roadmap to getting acquired as a way of competing. The exit becomes a scaling mechanism.

My biggest takeaway from watching the interview is how Manus approaches PR and comms with a long-term view. From the initial launch video—which was scripted by the co-founders not outsourced— the company was founder-led and designed for long-tail relationship value in the tech community on both sides of the Pacific.

Peak used the phrase 广结善缘, “broadly sowing seeds of goodwill,” to explain why Manus blew up at launch and why it attracted genuine interest and coverage quickly. He named dropped Patrick Collison (CEO of Stripe) and Jack Dorsey as early users of Manus.

The premise is quite simple but rarely done well: build goodwill over years by consistently showing up for other builders, sharing insights without immediately extracting value, and treating reputation as compounding capital. This mindset, unfortunately, isn’t the norm. Many AI startups in China, and many U.S. startups with Chinese founders, misread influence as a commodity and confuse press releases with real endorsement. Manus treated earned validation as relational, and also hyper selective about choosing opportunities to engage. In the process, Manus cultivated relationships with technical opinion leaders with meaningful followings on X, model ecosystem partners, and journalists who actually shape taste inside the community. Influence becomes a distribution network instead of outsourced to the GTM or growth marketing function.

That focus on influence showed up in how Peak talked about the company’s leverage over model providers. In the interview, he spent significant time describing Manus’s influence on feature development across model vendors like Google and Microsoft. He attribute that influence less to charisma and more to bargaining power: Manus was, by his account, a meaningful paying customer and feedback partner, which created real pull with providers.

tl:dr Manus treated influence as an asset, and that is the kind of reputation asset Meta bought.

China shedding in 2026

I have been tracking China Shedding as a signal since early 2024, from Temu trimming parent-company references, to TikTok trying to prove it is American enough, to VCs restructuring to sever China exposure.

My thesis then was that attempts at a dual narrative (to be one thing in China, and another globally) to fix perceptions in the United States carry a different long-term risk. The more a company distances itself from its Chinese identity, the more it can invite suspicion from Beijing that it is exporting talent, technology, and legitimacy away from China.

The Meta–Manus deal does not disprove that thesis. It updates it for the AI era. China shedding and Singaporization work as long as the narrative fits neatly inside “American tech leadership” framing and the company over-communicates separation so hawkish rebuttals can’t gain traction. Meta’s decades of DC lobbying turn that communication into a shield. Manus’s founder-led clarity turns it into a story that can travel and a playbook to emulate.

What makes Manus feel like a turning point is also what makes it feel like it could be the last of its kind. In China, the reaction is already politically and emotionally charged because it signals a path for ambitious Chinese AI companies to follow.

Manus also exposes an uncomfortable truth: for young AI companies, the market, the validation, and the exit pathway increasingly sit outside China, and the price of entry is a thorough China-shedding posture.

If more companies try to replicate the Manus playbook, Beijing has every incentive to raise the cost of that choice through export-control and tech-transfer enforcement. The U.S. side may treat China shedding as a compliance success. The China side may treat it as a strategic and reputational risk.

That tension is the next chapter of the story.

The "concentrated superiority in a domain" framing is spot-on - Manus basically treated acquisition as a competitive strategy from day one. What I find most intersting is how they weaponized influence (广结善缘) into actual bargaining power with model vendors, not just social capital. The timing thing is probabyl underrated too; dropping this during holiday deadzone when DC is quiet was absolutley genius if intentional.

Interesting! How do you see the reaction from officials in the mainland? Was a story also created to sell the local success or did manus miss that?