How My Foam Rollers'WSJ Debut exposes Temu's Bigger Issues

WSJ A-hed cameo, mini Temu purchases, de minimis value & parcel economics

Dear readers,

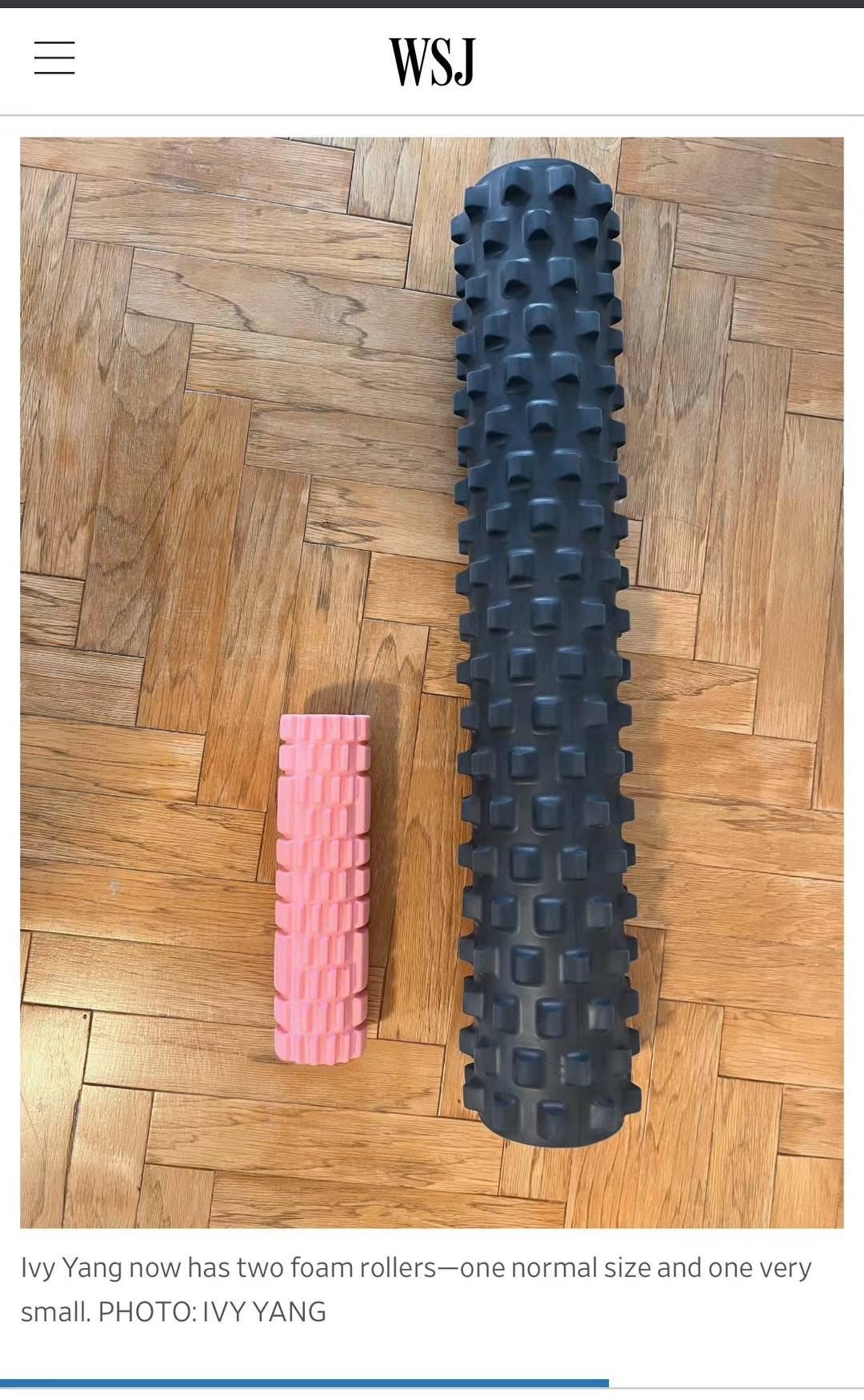

This week, I might just have peaked in my PR career — my foam rollers made it in the WSJ's front page A-hed Column.

The media inquiry from WSJ’s Katie Deighton was straightforward:

Why are the likes of Temu, Shein, Amazon etc. selling tiny stuff and badly labeling it as such?

I have several theories, and the growing media interest suggests rising reputational risks for Temu, which could notably impact its international market expansion.

Before going into detail about de minimis value and duty taxes, I want to introduce a new framework to look at cross-border e-commerce platforms in their feverish sprint to capture market share: parcel economics. It is the arbitrage of profit margins, shipping efficiency, and the expansion of the platform growth.

At the heart of the issue is margin.

The race to the bottom on prices is the basis for the relationship between the platform and sellers. Shipping mini versions are a result of the struggle for margin. In this reality of low-priced, thin-margin platforms, sellers are forced to incorporate risk and potential reward into their calculations; thus, the more they can sell, the better their chances of recovering their investment and turning a profit.

Stuffing more units into one parcel means sellers can avoid paying some duty taxes if their parcels' presumed value is below the de minimis threshold. Consequently, opting to fill shipments with smaller, lighter items instead of their full-sized versions can lead to better sales margins when considering the units sold and shipping costs.

This is probably why, in December last year, Temu issued a new platform rule for sellers called “Product weight and volume filling rules” 商品重量及体积填写规则. Per these guidelines, sellers face financial penalties for any discrepancies in reported product weight or volume. The onus is on the sellers to ensure accuracy, with the penalty formula being as precise as it is punitive — a 10 yuan fine for every 50g of discrepancy per order. This is especially significant considering Temu’s low price point.

Temu and its suppliers: a symbiotic and contentious marriage

The platform leverages its pricing power to its advantage, pressuring suppliers into agreeing to remarkably low prices — a dynamic I have previously analyzed.

Temu's PR Strategy of Saying Very Little

Greetings and salutations! I hope you are relishing the beauty of fall wherever you are. The past few weeks have been a whirlwind for me personally and the world at large. I hope you are keeping your loved ones close and gathering strength from all the places you can find it.

Meanwhile, suppliers have counter strategies to maintain their margins, often treading in ambiguous territory. With great power comes great responsibility—as cross-border e-commerce companies adopt a "full-service model," they will increasingly shoulder the responsibility of addressing consumer dissatisfaction and the potential legal and compliance issues that emerge from avoiding duties and offering substandard products.

I grew up in the '90s, and "Honey, I Shrunk the Kids" was an iconic film. I can't help but draw parallels between the movie's underlying message and Temu's circumstances. The film, in its essence, is a metaphor for the trials of growing up and finding one’s place in the world. Isn’t Temu on a “hero’s journey” to find its own equilibrium and platform-market fit?

The reputation risks of de minimis and mini things

Temu’s contribution to owner PPD’s total sales was likely less than 1% in Q2, according to Bloomberg analysts cited by DigitalCommerce360. But conflicts over truth in advertising and the de minimis value—already a contentious political issue—are likely to affect PDD more significantly than any potential revenue gains. There are heated discussions about the value of de minis value, a byproduct of opening up and facilitating global trade. We live in a very different geopolitical climate now.

The de minimis rule allows imports with a value of less than $800 to enter the country without being subject to duties as long as they are packaged and shipped to individual consumers. The Select Committee on the Chinese Communist Party said in a report that Temu and Shein, the two companies alone, are likely responsible for more than 30% of all de minimis shipments entering the U.S. each day. There is a political debate over proposals to lower this value threshold or restrict certain countries (read: China) from this duty-free privilege. It is expected to be a key issue of substantial trade dispute in Congress this session.

In addition to issues with duty taxes, intellectual property violations are also issues Temu can no longer dodge. Temu sellers are allegedly stealing text and pictures from Amazon, and Temu’s parent company PDD has already made it on the Notorious Market List, an annual report published by the United States Trade Representative that identifies online and physical marketplaces known for engaging in, facilitating, or turning a blind eye to counterfeit and pirated goods.

As a subsidiary of PDD 0.00%↑, a U.S.-listed company, Temu can expect its business practices to attract closer examination from shareholders, regulatory authorities, and the press as it becomes a bigger revenue contributor to PDD. With this backdrop, the compliance criteria for its U.S. and European-based entities will likely become more stringent, and this is just the beginning.

On a brighter note…

Back to how my foam rollers made it to WSJ. The A-hed column began in 1941 and has always been the business publication’s “funny page.” It’s about “lighten up. Relax. Don't take everything so seriously. Read a few A-heds.”

So, towards the end of chatting with Katie—most of which is the basis for this post—I shared a personal, silly anecdote. I, too, fell for Temu’s illusions and bought a foam roller so small it became a toy for my 2-year-old. It was an amusing twist that capped off the A-hed story perfectly.