Once a Year on Red Note: Are TikTok Refugees Becoming Digital Migratory Birds?

Red Note Signals #6 in light of the recent TikTok news

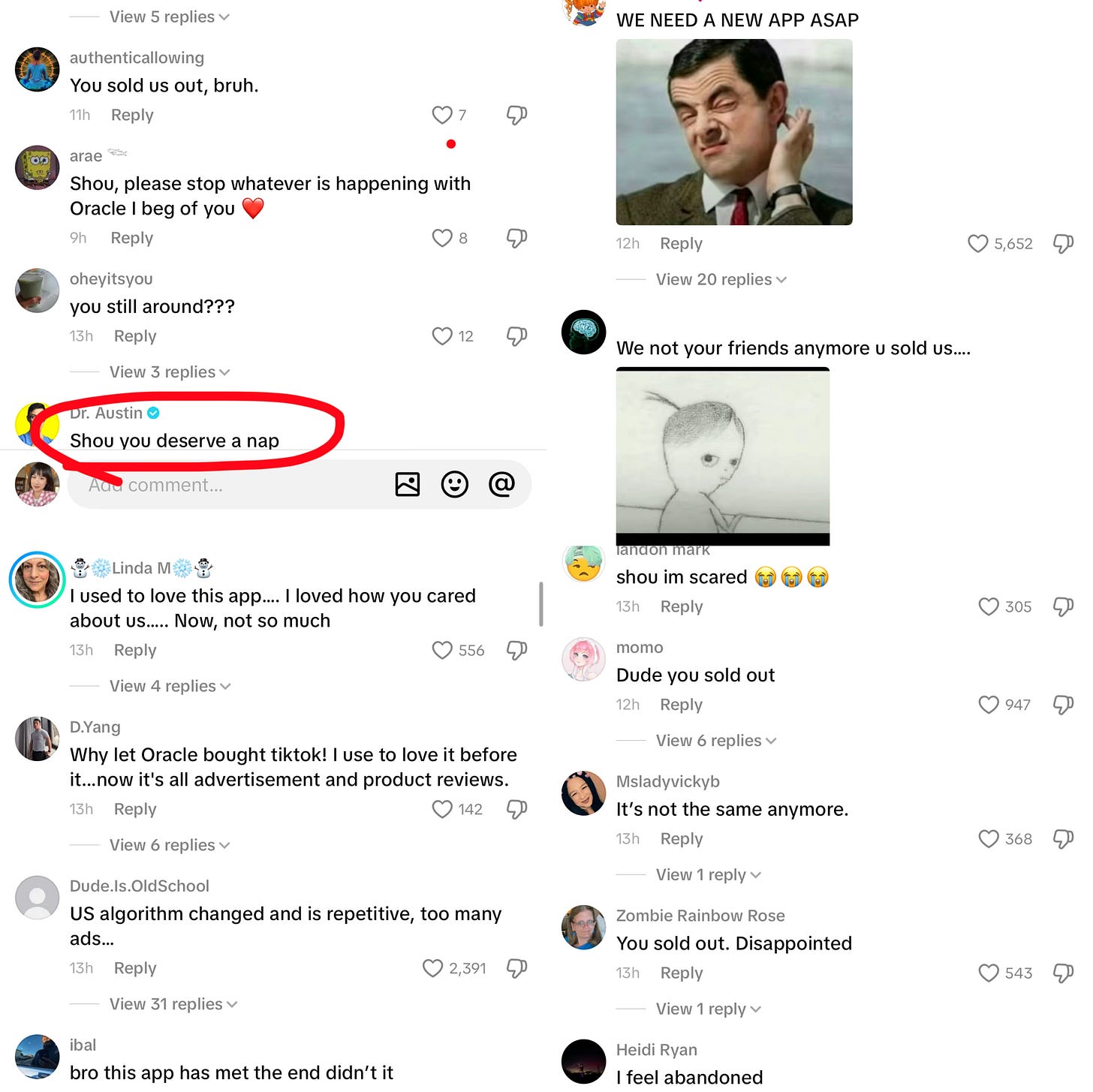

After TikTok announced it’s now “officially American,” TikTok CEO Shou Chew’s comment section flooded with worried users.

CNBC reported that the daily average of U.S. users deleting the TikTok app has increased nearly 150% over the past five days compared with the previous three months.

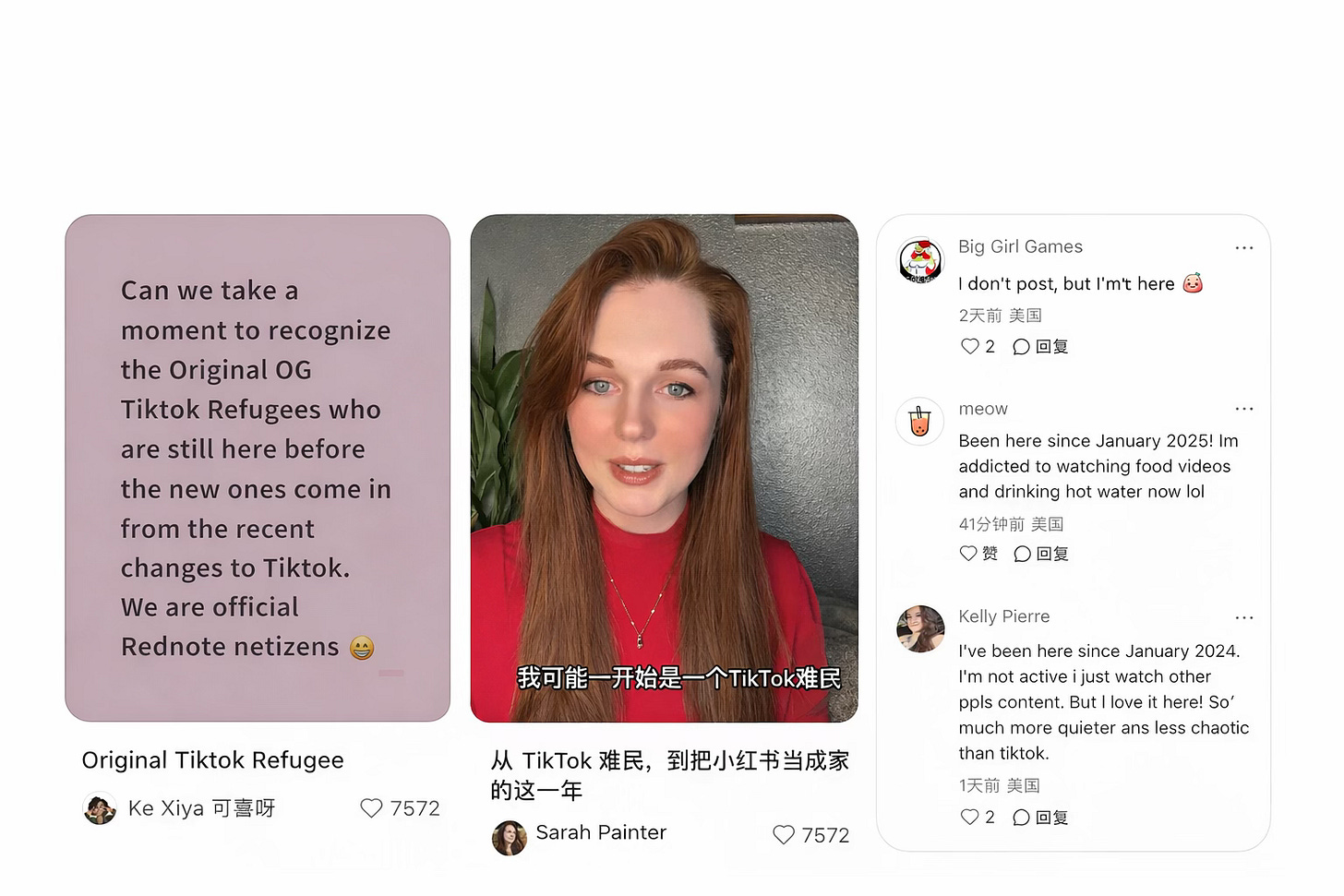

Last week, before the TikTok U.S. joint venture announcement, I made a TikTok about the one-year anniversary of the Red Note refugee moment, and the close to 200 comments became a live focus group of TikTok users who are also on Red Note.

My favorite comment came from someone who said she moved to China because of Red Note.

There were a few recurring themes from the refugees/Red Note users :

a shared sentiment that Red Note feels calm, peaceful (I don’t know about that…)

Red Note U.S. userverification is inconsistent, accounts get locked, and recovery is close to impossible.

The feed is also getting noisier, more obvious AI slop. (I’m not seeing that in the Mandarin side of Red Note)

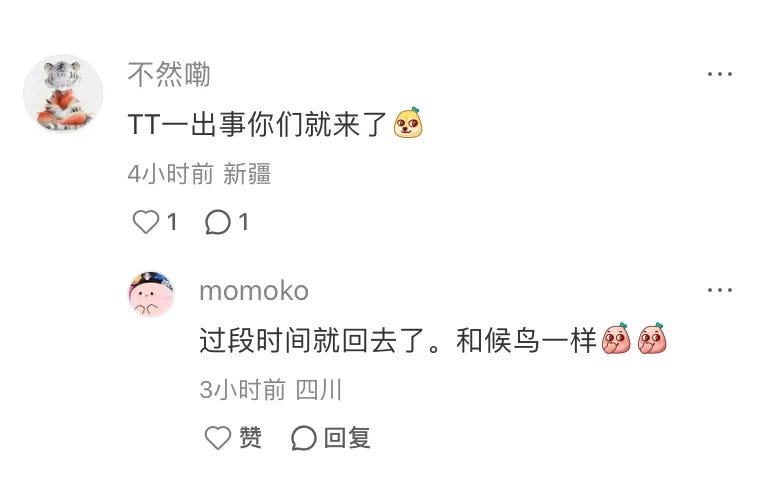

But as Peiyue writes, Red Note has not replaced TikTok as the go-to app; the irony is that, after TikTok has become a true American app, users are once again looking for an alternative, like the swallows who migrate to warmer locales when winter comes.

Once a Year on RedNote: Are TikTok Refugees Becoming Digital Migratory Birds?

By: Peiyue Wu

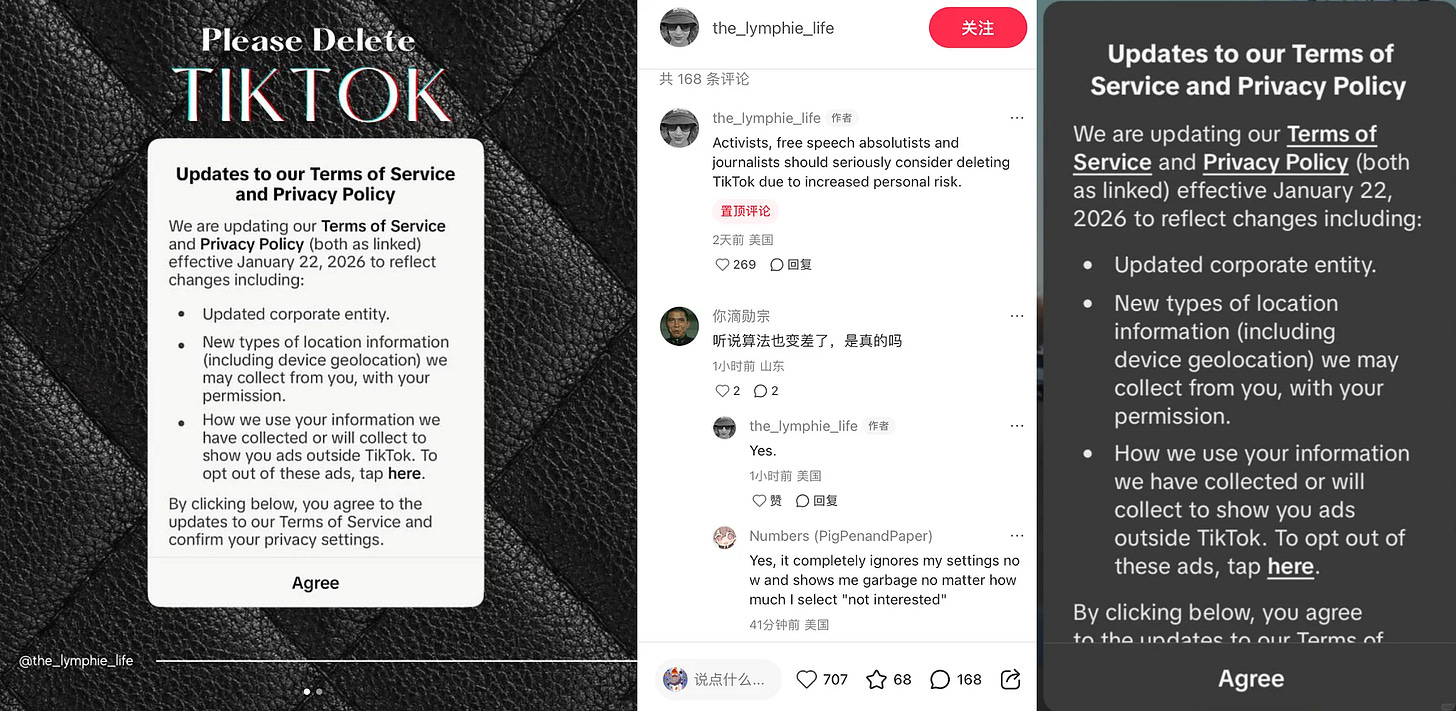

Just as the first wave of “TikTok refugees” on RedNote reached its one-year mark, another wave arrived. Last Thursday, American users once again crossed the Pacific in digital form. They set up new accounts, posted awkward bilingual introductions, and greeted Chinese users with photos of their pets.

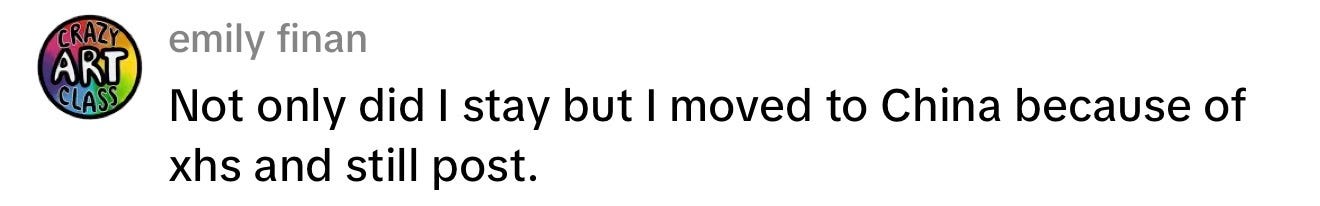

On January 22, ownership of TikTok’s U.S. operations was officially transferred to an American entity. That morning, U.S.TikTok users were greeted with new terms to accept.The language in the new policy was more sweeping, and TikTok would now collect more precise location data from its users.

Technically, this wasn’t unprecedented. Instagram, X, and other major platforms track similar information. Yet when those companies updated their policies, few people reacted. With TikTok, panic spread almost instantly.

Since the U.S. government announced last September that TikTok would change ownership, the internal adjustment has been read through a political lens. The timing of this update also worked against the company. Public anxiety was already high following the fatal shooting of Renee Nicole Good in Minnesota amid heightened ICE raid activity.

Under the new policy, TikTok claimed the right to collect what it called sensitive data, which included race, religious beliefs, and citizenship or immigration status. New rules also covered sexual orientation, gender identity, and mental or physical health diagnoses

For many users, especially minorities and undocumented immigrants, the new reality felt like data was being weaponized to be used against them.

Last year, the TikTok refugee trend was a protest against what many saw as the U.S. government’s hypocritical claim to protect data security. This time, the outcome struck users as almost darkly ironic. “They are doing exactly what they accuse China of doing, ” one user commented on an Instagram post warning of the risks behind the policy change.

As if to add fuel to the fire, TikTok began glitching. On Sunday morning, users reported trouble logging in. Videos failed to upload or publish. Some said their For You pages kept recycling content they had already watched, even after marking it as not interesting. TikTok blamed the problems on a power outage at a data center.

For others, another major concern about the platform had surfaced earlier. Censorship.

On January 5, Dylan Page, better known as News Daddy, announced that he was temporarily leaving TikTok. With more than 18 million followers, he is one of the platform’s most influential news creators. Page pointed to increased censorship and a sharp drop in views during coverage of major geopolitical events, including the U.S. government’s capture of Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro. According to him, some posts were delisted or deemed ineligible for recommendation.

Despite his announcement, Page continued posting on TikTok. An account widely believed to be his Red Note profile was created during the first refugee wave last January. After uploading four posts adapted for Chinese audiences, it went quiet. Over the past few days, even as a new wave arrived, the account remained inactive.

That’s part of the reason the TikTok refugee movement didn’t seem to last beyond the initial hype last year. Few major TikTok creators have fully committed to Red Note to make the transition meaningful.

Compared with a year ago, this new wave feels quieter on the Chinese side. Red Note has not aggressively pushed refugee content to Chinese domestic users. In comment sections, only scattered Chinese users appear (one comment jokes that these foreign visitors seem to return once a year, like migratory birds).

Are the TikTok refugees birds or here to stay?

Most interaction happens among the refugees themselves on Red Note. They find one another, talk in the comments, and explain why they have grown attached to a calmer and less performative online space. Longtime users share what they have picked up over the past year, from basic traditional Chinese medicine concepts to recipes they now cook at home.

Has Red Note changed much for the U.S. market in the past year? Not really. Monetization tools such as livestreaming are still unavailable to American users. The platform does not reward constant self-expression as U.S. creators expect.

That limitation may explain why many TikTok refugees remain invisible.

The ones who stick around aren’t always the ones posting. They mostly observe, and without a clear monetization pathway, there’s little reason to engage. Over time, Red Note just became a new habit.

In recent weeks, memes like “You met me at a very Chinese time of my life” have gone viral across Western social media platforms, often accompanied by ironic performances of drinking hot water or wearing the now-iconic Adidas Chinese jacket. These moments spread fast, but they just scratch the surface. By contrast, the TikTok refugees who remain on Red Note point to a different kind of cultural encounter, one built gradually through lingering rather than spectacle.

Taken together, the two waves of TikTok refugees tell a broader story. They are not really about China. They reflect a growing unease among U.S. social media users about surveillance, censorship, and the government that oversees them. In seeking refuge from one system, users drift into another not because it promises freedom, but because it offers an alternative that keeps up with the dopamine reward loop.