Red Note Signals #2 How an “Acquired” Italian Luxury Brand Stays Milanese in China

GIADA, a Chinese-Italian brand’s emotional-capitalism marketing playbook

China is already complex enough on its own, and figuring out what really makes Chinese consumers tick has become an ongoing preoccupation for brands and companies. The usual playbook — localize, empower China teams, respect cultural norms — is now just the baseline. What’s more interesting are the strategies to reach and grow customer loyalty, all with distinct Chinese characteristics.

I first came across GIADA’s mini art-history series while scrolling on Red Note. I lived in Florence for a year, so Renaissance art has a permanent claim on my heart. When I mentioned this campaign to Peiyue Wu — my partner in tracking Red Note signals, and an art history major (she’s endlessly cool) — Peiyue immediately saw it as a fascinating example too.

Below is a deep dive into how GIADA — a Chinese-owned, Italian-positioned brand — courts the minds and hearts of Chinese consumers, and the tensions that come with it. The brand is also waging a second, almost contradictory fight: staying aspirational for China’s middle class just as Western luxury fatigue sets in, budgets tighten, and “China-pride” guochao narratives start to rewrite what status looks like.

Below is the second installment of Red Note Signals, our series tracking how Red Note’s feed captures China’s shifting consumption trends and social mood.

You can read our first post on self-diagonosing ADHD on Red Note below.

How an “Acquired” Italian Luxury Brand Stays Milanese in China

By Peiyue Wu

The new playbook for attracting China’s middle class is no longer about gigantic billboards of scantily clad caucasian models or signing A-list Chinese actresses as brand ambassadors. The new formula is subtler, more cerebral: hire an art curator to produce art history mini lecture series on Red Note, or launch a podcast hosted by a celebrity journalist, and invite women with polished international credentials to talk about career development, personal growth, and ambition.

This is how GIADA, a Chinese-Italian brand that sits comfortably on the ground floors of China’s high end malls such as Wangfujing, right next to Chanel, Dior, and Gucci, is engaging with China’s increasingly sophisticated consumer base. You won’t find many Giada stores outside of China. For years, Chinese shoppers walking past GIADA’s boutiques and campaign posters probably just assumed it was yet another obscure European label they simply weren’t cosmopolitan enough to pronounce. Few realized the brand is actually controlled by a Shenzhen-based luxury mogul.

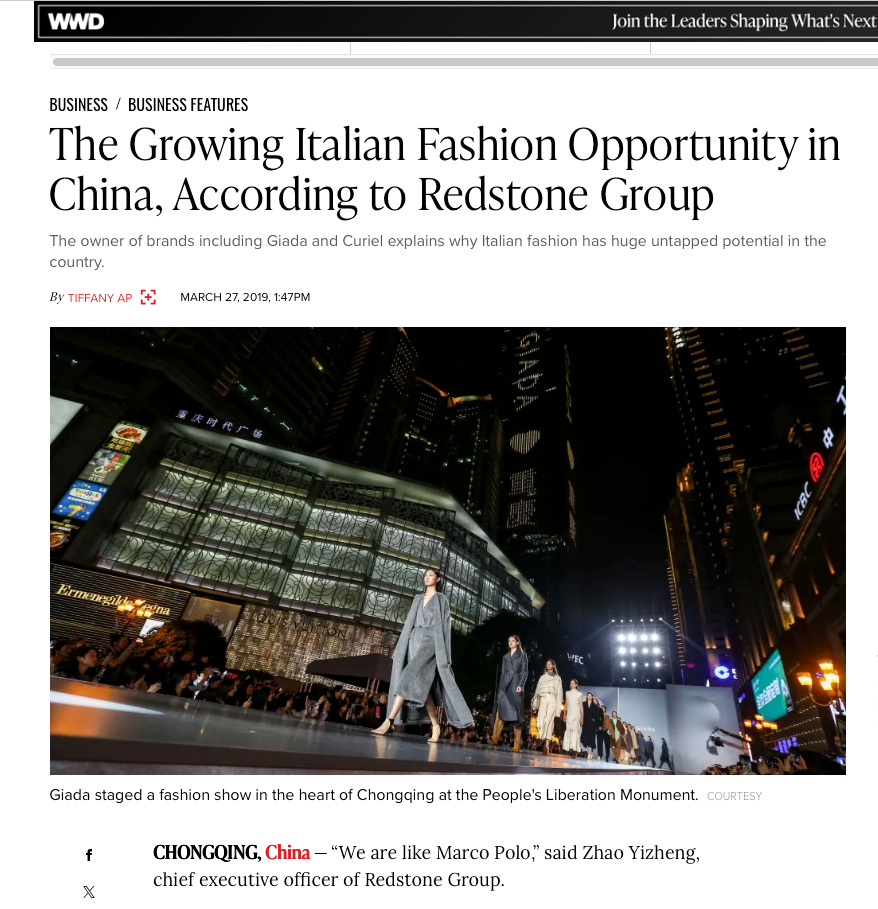

Technically, GIADA is Italian. Founded in 2001 by Rosanna Daolio, a former Max Mara designer, the brand was taken over in 2011 by its Chinese partner, the Redstone Group – though the company is careful to describe the transition as a “partnership,” not an acquisition. The brand continues to emphasize its “Made in Italy” credentials, with Gabriele Colangelo as creative director, while China HQ, the company says, oversees marketing and operations. Under a similar arrangement, Redstone now operates several other Italian labels.

That Italian identity is the brand’s core currency. Without it, GIADA risks being dismissed as just another domestic label merely posing as European – a suspicion that frequently surfaces on Chinese social media.

Yet the brand is also fighting a second, seemingly contradictory battle: how to stay desirable to China’s middle class at a moment when Western luxury excitement is cooling, wallets are tightening, and the rise of “China-pride” Guochao narrative is reshaping consumer psychology.

GIADA’s answer is a carefully curated form of emotional capitalism, one that China’s middle class, especially women, finds hard to quit. Those women are drawn to the brand’s promise of valuing culture and depth. These aspirational qualities are what highly educated, career-oriented, ambitious women want to be respected for as they navigate a male-dominated society in China. Even as “made in China” climbs the global ladder, the allure of Western art history and elite education continues to exert a powerful pull.

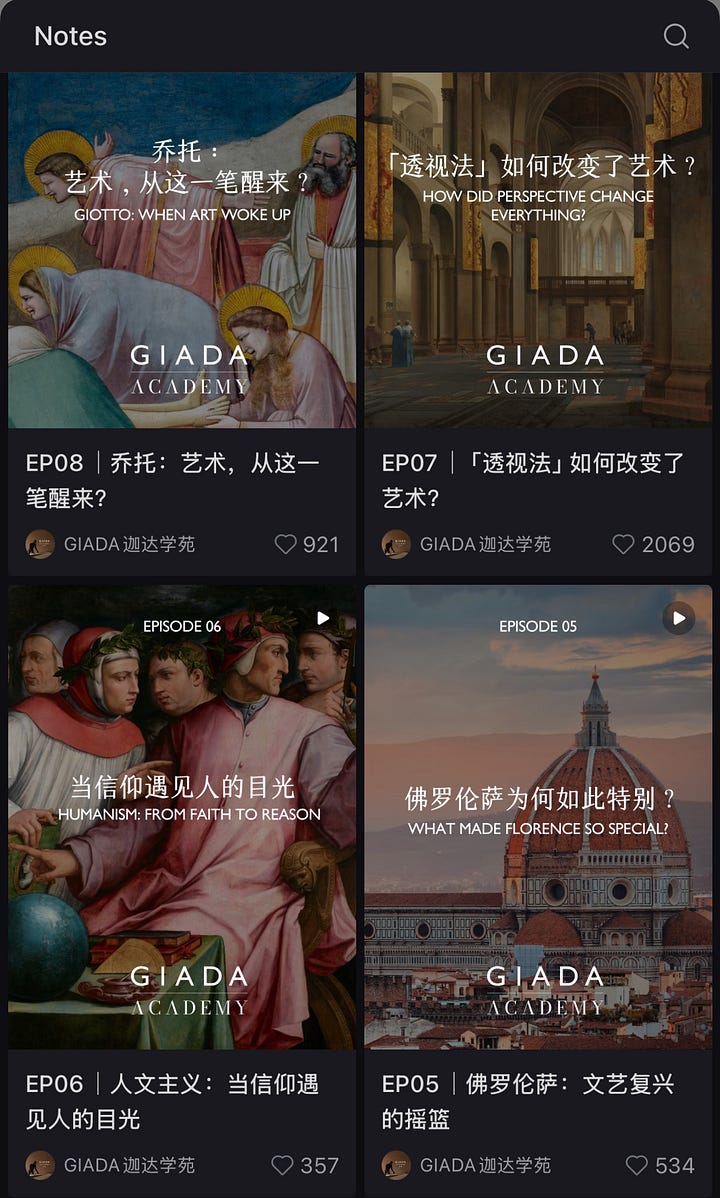

The Rednote Art History Academy

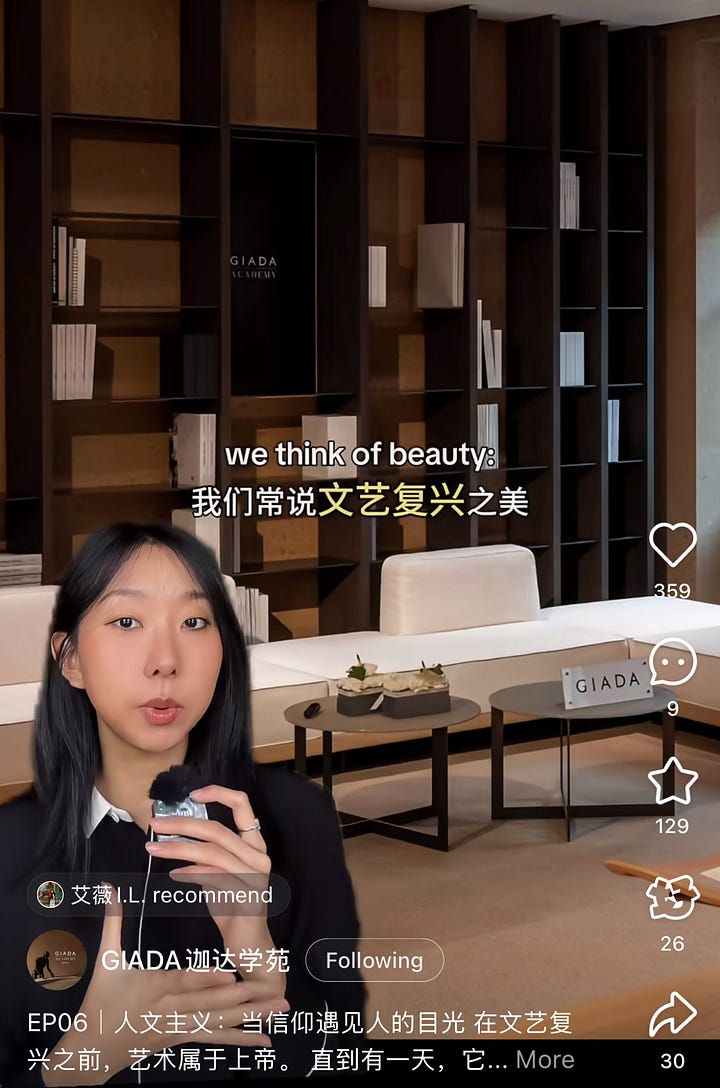

Launched on Xiaohongshu in September, “GIADA Academy (GIADA 迦达学苑)” has already posted more than a dozen short videos hosted by Ivy Li, an art-history creator. In four-minute episodes on the Medici family, Botticelli, or Renaissance Florence, Ivy layers ornate art-historical vocabulary over rapid-cut sequences of classical paintings and architecture.

Ivy is not Italian – which itself underscores that GIADA is not simply casting her for a look, but foregrounding her depth of knowledge. She is not just an influencer, Ivy runs her own curatorial and art advisory practice; GIADA is, in effect, borrowing her intellectual and professional credibility. She speaks with a soft, almost hypnotic warmth, with a precise articulation on the topics of art and beauty.

The Red Note account now has over 27,000 followers. For a young account barely over three months old, the numbers are strong.

A Luxury Podcast and a Journalist CEO

GIADA’s most effective campaign to date has been its podcast series “Take Bloom on the Rock (岩中花述).” Engagement surged after the brand brought on veteran interviewer Chen Luyu in its third season and the branded podcast has more than 2.5 million subscribers.

The guest list signals cultural prestige: Harvard Law graduate and debate champion Zhan Qingyun, for example, spoke about her years at Harvard and her admiration for Ruth Bader Ginsburg, who as controversial as she was, the second woman – and first Jewish woman – to serve on the Supreme Court. The female podcast guests are dressed in GIADA clothing and the aesthetics speaks louder than any advertisements.

Other luxury houses such as Loewe, Louis Vuitton, Prada among them have experimented with podcasts, either in advertorial format, or produced podcasts but only to abandon the format after a few episodes. GIADA remains one of the rare brands that has managed to turn podcasting into sustained cultural capital.

Perhaps it has something to do with GIADA’s journalist-turned-operator CEO. GIADA’s CEO Zhao Yizheng began as a journalist and photojournalist in the 1980s before shifting into luxury-focused investment in the 1990s. He describes the brand’s mission as conveying Italy’s culture, aesthetics, and intellectual heritage “through the careful lens of a reporter, the eye of a journalist.”

After consolidating its presence in China and keeping its Milan flagship, GIADA opened a Boston store in 2020. Zhao said in an interview at the time that they are “planning to open in New York in 2021, then in London, Paris and then in Italy, Rome, Venice and Florence to bring Giada into the world.”

So far, none of those plans have materialized. But using cultural capital to sell clothes seems to still be an important pillar of the brand strategy.

A Narrative Trap?

This raises a question: can GIADA ever speak with the same authority beyond China’s borders.

GIADA’s unique strength is its near-magical fusion of Italian heritage with a feminism interlaced with admiration for Western-educated, culturally influential Chinese women, a blend that simultaneously defines the brand at home and complicates its ability to translate that identity globally.

In a way, GIADA feels like a treaty between two aesthetics: Italian discipline wrapped around a Chinese sense of narrative.

This is so utterly cool…

This was fascinating. I'm so curious about the podcast element, in the podcast bio it says "见识过 世界也体味过生活的GIADA WOMAN聚集在 这里进行自由表达,交流人生思考,讨论专专 于这个人生阶段的女性议题,传递出坚韧与温 柔并存的女性力量." Obviously being a Chinese production, I wonder what their take on feminism is, and how deep or for they're willing to go on a lot of subjects. Have you listened to any of the episodes? Also, are they any good!