Red Note Signals #5 When Chinese Virtual Boyfriends Go Global, Fans Dispute Their Chineseness

Peiyue and I go very deep on Chinese virtual boyfriends going global and Red Note Feminism

I downloaded Love & Deepspace last night for “research” ahead of this. In China this past week, the “Are You Dead” app went viral: users check in daily, and if they miss two days in a row, the app contacts an emergency contact. I spoke with the Guardian’s Amy Hawkins about its sudden popularity. There is a common threads in the two apps: one is about adventure & love, and the other about death. They both reflect a growing global loneliness economy.

Amy and I talked a lot about Red Note feminism, which can be understood as a collective search for meaning in a reality where women express independence by rejecting traditional gender roles and values. One reason I think Red Note is so sticky is that it creates subcultures and a safe space where expression feels natural and authentic. At the same time, in the gaps once filled by real humans, technology increasingly steps in to provide emotional connections.

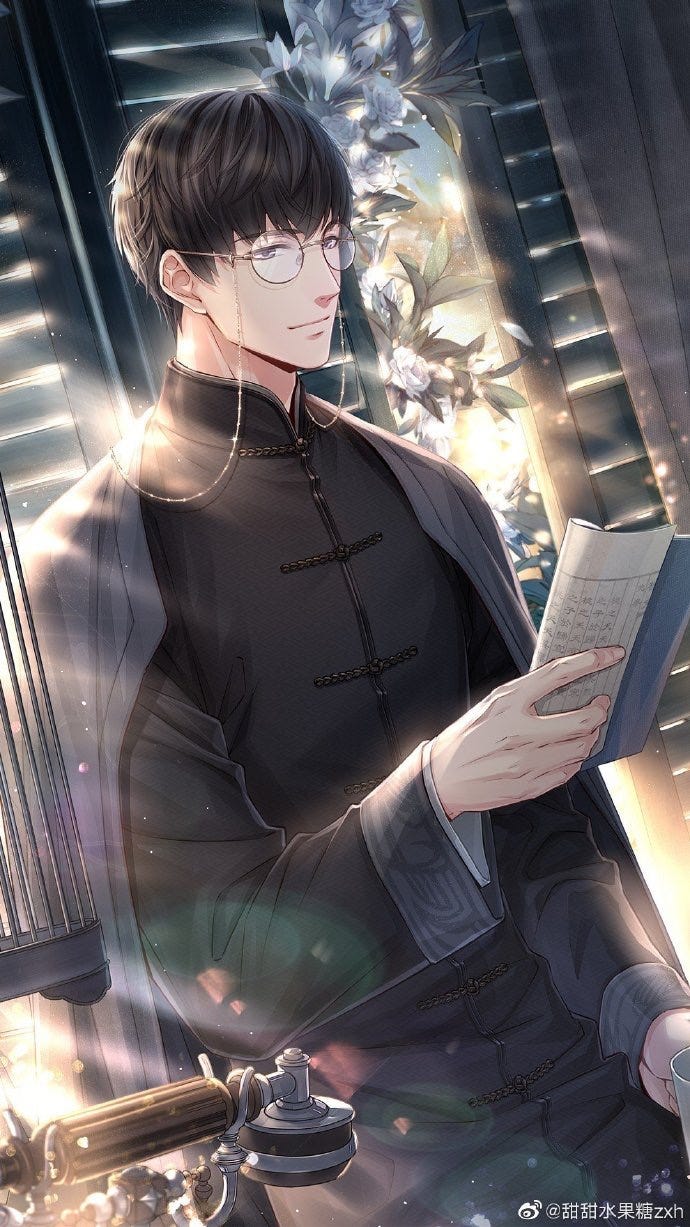

After a few hours with Love & Deepspace, I think I get it. It’s a hybrid of a dating sim and a light action RPG. I am a female “hunter” in a near-future world battling interdimensional creatures called Wanderers, while part of a storyline to build relationships with impossibly handsome male leads: Xavier, Zayne, Rafayel, Sylus, and Caleb. Each is tied to different factions and storylines I can influence, and the experience is not linear: I can like and leave comments on their WeChat Moments-style social feeds, text them, hang out at a cafe, or go battle some Wanderers together.

The game simulates how love develops in real life, and the relationship deepens as the storyline attemps to create shared progress and meaning. The difference is that instead of experiencing the ups and downs, and the fickleness of real world relationship, this entire process now plays out inside an app, with out-of-this-world perfect men with six-pack abs, perfect jawlines, and undivided attention that no human can compete with.

When Chinese Virtual Boyfriends Go Global, Fans Dispute Their Chineseness

By Peiyue Wu

In 2023, I wrote about Chinese women who fell in love with virtual boyfriends and attempted to bring those relationships into real life by hiring cosplayers to embody them.

The trend took off shortly after China lifted its zero-COVID policy and was largely organized on RedNote, where otome game players share screenshots, write emotional diaries, and openly recruit cosplayers.

In cities, it became increasingly common to see an ordinary young woman walking through shopping streets beside a carefully constructed “anime man,” often played by a female cosplayer wearing platform shoes and artificial chest muscles.

Many players deliberately chose female cosplayers to avoid the physical risks they associated with interacting with men.

To outside observers, the scenes were easy to misread as an extension of anime fandom. China has long been influenced by Japanese ACG culture, and cosplay itself is nothing new. What was new was how these “leisure hobbies” are reshaping a generation of women to imagine intimacy, romance, and emotional labor.

At the time, I interviewed players ranging from teenagers who had never dated men at all to women in their thirties often labeled as “leftover women,” many of whom were exhausted from trying to make real-life heterosexual relationships work. Across age groups, the shared sentiment is disappointment with how men in China fail to meet their romantic expectations.

Recently, I decided to revisit the topic after realizing that Chinese-developed otome games such as Love and Deepspace had gained a far larger overseas audience than I had anticipated, particularly in the U.S.

While these games were initially targeted for Asian markets – especially Japan –, the U.S. has become one of their largest growth regions. As they moved beyond anime circles and reached players unfamiliar with Asian pop culture, a peculiar debate began to surface on both Chinese and Western social media: Are these male characters Chinese, or are they white?

One viral post even used AI tools to analyze character portraits, assigning percentage breakdowns of imagined racial “bloodlines.”

When these discussions appeared on Chinese platforms like Red Note, they sparked nationalist sentiment almost immediately. Chinese fans expressed a strong sense of ownership over the characters, frustrated that overseas players would enjoy the games while denying the characters’ Chineseness. A common complaint was “even when they like the game, they still don’t want the men to be Chinese.”

Even as interest in real men declined, pride in nationality remained intact.

Personally, I find it strange that so much energy is invested in arguing over the ethnicity of fictional characters. But it is also clear that real-world anxieties about race, geopolitics, cultural hierarchy, and recognition are being projected onto these virtual romances.

To better understand this tension, I reached out to an African American player named Mari, who goes by the online name “Fangirl Travels,” with whom I had been in contact since my 2023 article. Back then, she had found the piece circulating in a Twitter fan group and contacted me to introduce herself as a player. Until then, I had barely been aware that these games had meaningful non-Asian player bases at all.

When I asked her about the ethnicity debate, she acknowledged that it exists, but offered a nuanced distinction. She sees two very different behaviors among overseas fans.

The first group playfully assigns different ethnicities to characters in an affectionate way. These fans fully understand that the characters are Chinese and have no issue with that. Calling a character “Brazilian” or “Black” can function like a joke of intimacy, she said. “Like how someone might introduce their boyfriend of a different race to their family, and he is called ‘an honorary (insert ethnicity here)’.” She also points out that this can also stem from a lack of romance games with certain races and ethnicities, such as Black and Latino.

The second group, however, actively tries to erase the Chinese ethnicity altogether. That, she said, felt wrong and unsettling.

Mari herself plays Love and Producer (also known as Mr. Love: Queen’s Choice). Her favorite character is Lucien (Xu Mo). “I love that he is Chinese,” she told me.

When I looked up Lucien, I was struck by how closely he resembled a popular Chinese social media archetype: the “hot nerd” – intellectual, restrained, quietly intense. I asked Mari which aspects of his attraction felt universal, and which felt tied to specifically Chinese masculinity. I explained that traits like emotional restraint and diligence are often framed in Chinese discourse as uniquely Chinese forms of desirability.

She admitted that she didn’t feel qualified to identify “Chinese masculinity” as such, having had limited contact with Chinese men in real life. Instead, she described Lucien as a rare hybrid archetype: flirtatious yet reserved, dark-haired, intelligent, glasses-wearing. “Those traits don’t usually coexist in one character,” she said. It was the combination, rather than the nationality, that captivated her.

Her answer led me to a broader question. As Chinese otome games expand overseas, they are often framed as “cultural export,” a label that carries political value. In China, gaming is a heavily scrutinized industry due to concerns about addiction and youth influence. Otome games, in particular, can be seen as threatening traditional values surrounding marriage and gender roles, which leads to a low birth rate. A similar title, Glow, an AI companion app developed by MiniMax, has already been banned in mainland China. (Unlike AI companion apps, most otome games are not built on open-ended artificial intelligence but rely primarily on scripted narratives.)

But if these games are packaged as “cultural export,” they gain legitimacy. Overseas success becomes a shield, helping them survive at home.

Yet are these games truly exporting Chinese culture? Or are they primarily adapting to global tastes?

Many of the male archetypes presented in those games and short dramas, such as the powerful, emotionally dominant “CEO-type” lover, are often assumed to be uniquely East Asian. In reality, they resonate strongly with Western female audiences as well, even though their society has higher levels of feminist consciousness. That makes me realize these traits are not strictly “Asian”, but are broadly universal. Meanwhile, the characters themselves are deliberately racially ambiguous, designed to allow players wide latitude in interpretation.

Mari’s perspective also highlighted another blind spot. When Chinese discourse talks about “the West,” it often implicitly evokes a narrow Anglo-Saxon racial archetype. In reality, Western societies are racially and culturally diverse, encompassing Black, Latino, Eastern European, and many other communities whose desires are far from fully served by existing romance games.

That diversity is more an opportunity than a complication. And it may ultimately matter more for the future of Chinese games abroad than the question of whether a virtual boyfriend is really Chinese at all.

To read previous editions of Red Note Signals: